Physician Suicide Awareness and the Lorna Breen Act

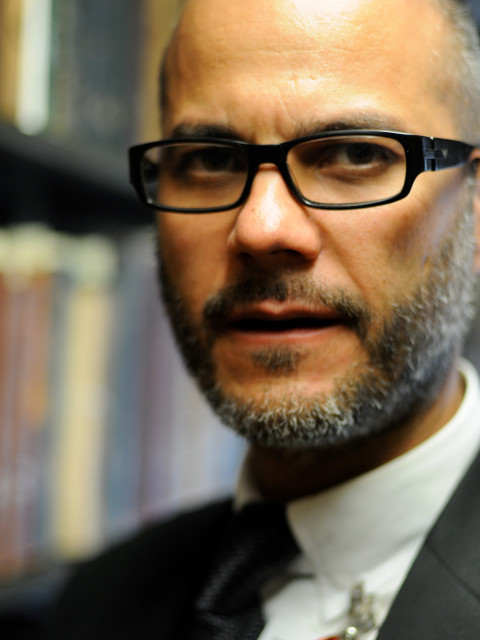

by MarkAlain Déry, DO, MPH, FACOI

Infectious Disease Specialist

September 21, 2021

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, the U.S. was facing a mental health crisis. A recent Johns Hopkins guide to suicide risk in the pandemic notes that the annual suicide rate in the U.S. has increased steadily over the past two decades. In 2019 it was 14.5 per 100,000 up from 10.4 per 100,000 in 2000.

According to the CDC, from 2006 to 2017, the suicide rate rose by 2 percent each year. That means there has been a 26% surge since 1999. In 2019 nearly 50,000 Americans died by suicide and there were over 1.3 million attempts. It is the 10th leading cause of death in the U.S. and the second leading cause of death in males under the age of 44. Today we can say assuredly that the pandemic – especially as it lingers on – is exacerbating this public health crisis.

Interestingly, the Johns Hopkins guide also points out that previous pandemics including the flu pandemic in 1918, the SARS outbreak of 2003, and the Ebola epidemic have all been associated with increased suicide rates. However, suicide is a bigger problem and can’t be blamed solely on the pandemic – although the isolation and fear it has created is certainly a major contributing factor. Suicide is part of the bigger problem of "deaths of despair" that includes alcohol related deaths and drug overdoses. These deaths of despair are being considered an epidemic within the pandemic.

Several risk factors are at play, including economic stressors, seemingly inescapable anxiety, social isolation, pandemic-related barriers to treatment, alcohol and drug abuse, and increased gun sales. This last point is important since guns are the most common means of suicide in the U.S. and interestingly the Harvard School of Public Health suggests there is a link between suicide rates and the prevalence of gun ownership – this is something we need to explore for a future video blog.

Interestingly there is a gender split in suicide rates between men and women. In comparison with women, men in the US are almost 4 times more likely to commit suicide. Almost 35,000 men die by suicide annually in our country – a man commits suicide once almost every 15 minutes. In 2019, nearly 70% of all suicide deaths were white males. When men commit suicide, they tend to use more violent methods in their attempts. Thus, unlike women, the chances of successful interventions are almost zero.

There’s no two ways about it. Suicide is a public health threat and a true epidemic. So, what can we as osteopathic physicians do to recognize the risk of suicide in our patients? What we do know is that asking high-risk patients – specifically individuals who have had previous suicide attempts - about suicidal intent actually leads to better outcomes and does not increase the risk of suicide. As we encounter our patients, things to consider in a patient’s history are intent, plan, means, availability of social support, previous attempts, and the presence of comorbid psychiatric illness or substance misuse.

As physicians, we should do what we can to activate support networks and initiate therapy for psychiatric diseases for at-risk individuals. Being alert to at-risk patients is part of Principle-Centered Medicine™ and treating the whole patient. Equally important is how we respond when we see a colleague in distress or showing suicidal ideations. That leads me to addressing another epidemic – that of physician suicide.

Last week was National Physician Suicide Awareness Day and we can’t let this go by without noting that too many physicians are depressed, burned out, and exhausted. In fact, it has been known for more than 150 years that physicians have an increased propensity to die by suicide. Back in 1977 it was estimated that on average the US loses the equivalent of at least one small medical school or a large medical school class to suicide. It is actually hard to have exact numbers due to inaccurate cause of death reporting and coding, but it is thought that approximately 300-400 physicians per year, or perhaps a doctor a day, dies by suicide. Of all occupations and professions, the medical profession consistently is near the top of occupations with the highest risk of death by suicide.

Many of you might remember the passing last year of an ER physician from New York – Dr. Lorna Breen who died by suicide. She had contracted COVID-19 and recovered. She went back to work to face what she described to her family as devastating scenes of the toll the virus took on her patients. To manage the onslaught of COVID patients, she worked multiple 12-hour shifts in a row and stayed late every day. She was in the thick of it early on in New York as ambulances regularly delivered COVID-19 patients to her hospital. Her family reported that she never slept and when they spoke to her on the phone they could hear the deepening distress in her voice.

She, like so many, was caught in the presumption that physicians are superhuman and we cannot show weakness. I applaud Dr. Breen’s family for standing up to make their daughter’s plight public. They set up the Lorna Breen Heroes’ Fund to provide mental health support to health care professionals. Additionally, due to their efforts, the U.S. Senate last month unanimously passed the Dr. Lorna Breen Health Care Provider Protection Act to help provide grant funding for suicide prevention and peer support for mental health care programs at health care facilities.

In a recent podcast from the ACOI that I encourage you to listen to, Dr. Julie Sterbank shares what we can do as colleagues to help each other prioritize our own self-care. She speaks from a place of knowing. She lost a colleague early in her career to suicide.

I encourage my colleagues to find ways to take time off when we know we need a break and to get professional help if you need to. There is no shame in reaching out for help. We need to be there for each other.

Sources:

- World Suicide Prevention Day: A Reminder to Business Leaders that Mental Health is a Matter of Life and Death

- ‘The dual pandemic’ of suicide and COVID-19: A biopsychosocial narrative of risks and prevention

- Male Suicide: A Silent Epidemic

- The Suicidal Patient: Evaluation and Management

- National Physician Suicide Awareness Day

- After Dr. Lorna Breen Died by Suicide in April, Her Family Took Up a Cause They Never Wanted