How the Expansion of Medicaid Affects Healthcare Inequities

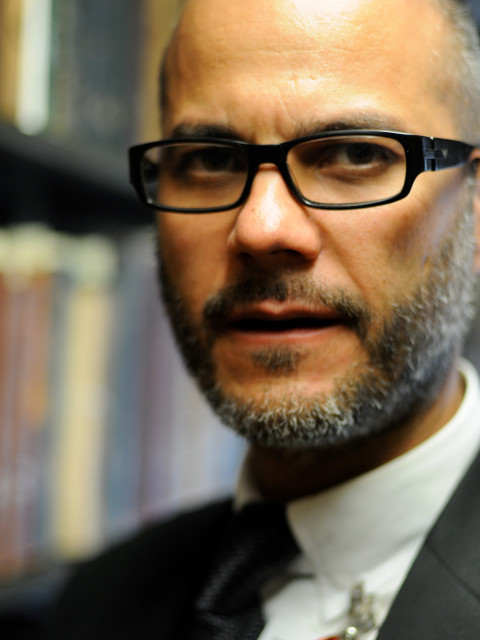

by MarkAlain Déry, DO, MPH, FACOI

Infectious Disease Specialist

December 22, 2021

Medicaid was authorized by Title XIX of the Social Security Act and signed into law in 1965 alongside Medicare. According to Medicaid.gov, all states and U.S. territories have Medicaid programs designed to provide health coverage for low-income people. The year 1965 was also the year immediately following the passage of the Civil Rights Act and the idea of Medicaid was to help improve access to healthcare as an important part of the battle to combat poverty and help vulnerable populations. Although the Federal Government establishes certain parameters for all states to follow, each state administers their Medicaid program differently, resulting in variations in Medicaid coverage across the country. From a public health perspective, that is where the problem starts.

I live in Louisiana. It’s a state that expanded Medicaid in 2016. A study reported that as a result, uncompensated care costs dropped 55% among the state’s rural hospitals. That’s good news! It turns out that hospitals are much better off in Louisiana because of that expansion than in the states (like Mississippi for example) who chose not to expand it. As a result, a new facility to help residents of Madison Parish, Louisiana access care for chronic conditions like diabetes and cancer is being built to relieve many of the burden of traveling up to 30 miles to a specialty clinic.

But just over the border in Mississippi, where the governor refused to expand Medicaid, the Jefferson County Hospital & Behavioral Health unit is struggling. They simply don’t have the budget to improve or expand facilities to improve care access. The reimbursement rates are too low to cover the costs. With a poverty rate of nearly 40% and unemployment rate at nearly 20% in Jefferson County Mississippi, it is exactly the sort of place where Medicaid expansion is necessary.

An economist for the state of Mississippi released a study recently that found that Medicaid expansion would actually be a boon to the economy and would likely add over 11,000 jobs to the state. In addition to reducing hospital costs for unpaid care, it would also likely pay for itself within 10 years. Regardless, it is not in place; Medicaid expansion has been outright rejected by the governor. This is the sort of scenario that creates a classic public health nightmare.

The Medicaid program, which matches federal dollars to state money to provide healthcare to the most vulnerable, creates a roughly dollar for dollar match. In Mississippi, for every $1 the state spends on Medicaid, the federal government spends nearly $5.50, which is a lot more than in any other state.

Let’s be clear that while the federal law mandates that states cover certain qualified, low-income groups, such as families, people with disabilities, seniors, pregnant women, and children, it is the state that ultimately decides who else is considered eligible. This lack of consistency from state to state is exactly how a Mississippi county has drastically different care access for vulnerable populations than a few miles over the border in neighboring Louisiana.

When states like Mississippi don’t expand Medicaid who exactly does it hurt? Those who are too poor to qualify for the subsidies available under the Affordable Care Act but who are not poor enough to meet the state guidelines to be Medicaid recipients. A ruling by the Supreme Court in 2012 that gave states the option as to whether they wanted to expand eligibility created that gap. Mississippi, along with eleven other states including Wyoming, South Dakota, Kansas, Wisconsin, Texas, Tennessee, Alabama, Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Florida are creating a public health nightmare for many of their residents by refusing to expand Medicaid.

I speak as both as an infectious disease physician and as a compassionate human being when I say that this makes no sense. I don’t understand denying healthcare to anyone. I speak purely logically when I say it makes no sense especially when the COVID-19 relief bill that was passed this past March included financial enticements for the 12 holdout states to expand Medicaid. The federal government has said that it will cover 90% of the costs for the newly eligible population, plus an additional 5% of the cost of those already enrolled. An analysis by the Kaiser Family Foundation estimated that the net benefit for these states would be $9.6 billion. But none of the holdouts are taking the government up on the offer.

The other part of the Medicaid and public health equation is us - physicians who won’t take patients on Medicaid. For many low-income people in the US, getting insured isn’t enough to actually get healthcare. It turns out that once eligible for Medicaid the next hurdle to overcome is finding a physician that accepts it. The reason, which many of you reading this know all too well, is that Medicaid billing is not easy.

A recent study found that providers run into more obstacles when trying to bill Medicaid than they do with other insurers, and that Medicaid payment rate amounts that doctors receive for providing services are on average lower than Medicare or private coverage. Almost 20% of the Medicaid claims that are made are never paid in full. This then turns into an administrative nightmare as providers try to sort out rejected or disputed claims. This explains some of the reluctance physicians have with accepting it.

There are also issues with providers who treat Medicaid patients differently. Dissecting this from a public health perspective , there is a study that was published in 2015 that found that in the U.S., people of color face disparities in access to health care and the quality of the health care received, finding that most health care providers appear to have implicit bias — basically reflecting positive attitudes toward Caucasians and negative attitudes toward people of color.

Another study published just last year in the New England Journal of Medicine found that algorithms used by physicians to make health care decisions are saturated with implicit racism that their designers were unaware of, but which often results in inferior health care for Black people. Black Americans who experience this bias and who happen to also be on Medicaid have the additional burden of not only finding providers that take Medicaid but also who don’t resent taking it and making less money. There are too many stories out there of Black patients being treated differently or who have physicians who are less than responsive to their needs – and while implicit and sometimes explicit bias is sometimes to blame, so is the underlying resentment of knowing they are not making as much money on Medicaid patients as they would on others.

Sources:

- ‘Poor folks trying to make it as best we can’: surviving Mississippi’s miserly healthcare system | Health | The Guardian

- ‘We don’t get treated the same’: Implicit racial bias is another barrier to quality health care - pennlive.com

- Medicaid is a hassle for doctors. That’s hurting patients. - Vox

- Status of State Medicaid Expansion Decisions: Interactive Map | KFF

- 12 Holdout States Haven't Expanded Medicaid, Leaving 2 Million People In Limbo | Georgia Public Broadcasting (gpb.org)