Gun Violence is a Public Health Threat

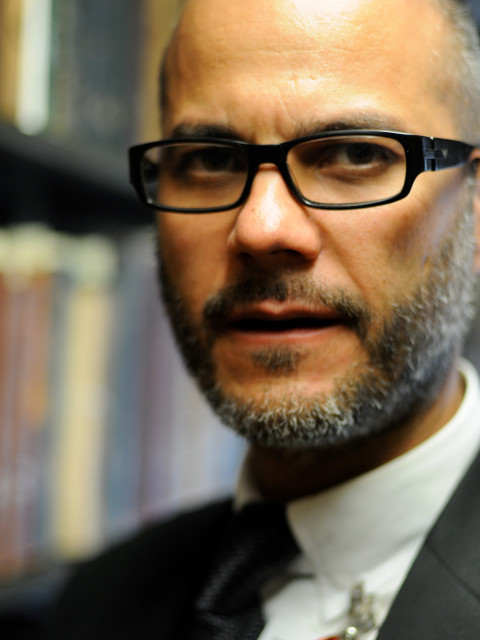

by MarkAlain Déry, DO, MPH, FACOI

Infectious Disease Specialist

November 16, 2021

I read a stat that blew me away the other day: in 2020, around 23 million guns were purchased. Yes, at the height of a public health disaster where many of us were focused on saving lives while the country was dealing with COVID-19, in the midst of the economic uncertainty that led to massive job losses and shutdowns, and while the country was reeling from the police violence that resulted in George Floyd’s murder, people went out to buy guns in droves.

There is an organization called Small Arms Analytics that measures gun sales. Not only is that number that they uncovered shocking, but consider that this number represented a 65% increase over 2019 gun sales. One can surmise that not only are people buying guns in droves, but more people are buying guns and more people are likely owning multiple weapons. If this doesn’t smell like a public health disaster in the making I don’t know what does. Not surprisingly, gun violence increased as a result. Over 19,000 people were killed in shootings and firearm-related incidents – according to the Gun Violence Archive (GVA) that’s the highest death toll in over 20 years and a 25% increase in homicides and accidental fatal shootings from 2019.

Additionally, 68% of homicide victims in larger cities are Black. On top of the disproportionate numbers of Black Americans dying from COVID and the police violence widely chronicled against Black Americans in 2020, Black Americans are also widely suffering from an increase in gun violence. While suicide rates went down overall in 2020, suicides actually increased among Black Americans. This comes as no surprise since studies have consistently reported that exposure to discrimination and repeated microaggressions is related to increased rates of depression among Black people.

Also in 2020, the number of mass shootings—where four or more people are shot and injured or killed—rose to over 600, representing a nearly 50% increase from 2019’s total. Time Magazine calls 2020 one of the deadliest years in US history, between the pandemic and gun violence. 2021 is shaping up to be about the same if not worse.

So how did 2020 end up creating conditions for such record-breaking numbers? And what can those of us in public health do about it?

The director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Gun Policy and Research said that 2020 was truly the "perfect storm" of conditions where "everything bad happened at the same time -- you had the COVID outbreak, huge economic disruption, people were scared." Another important point to note is that because kids were not in school, things like after-school programs and other violence disruption programs weren’t happening. Some also say that with 2020 being a contentious election year, gun purchases went up for fear that a new administration would change gun policies and restrict gun ownership.

It was also discovered that due to pandemic fears, people had their guns more accessible in their homes and changed how they stored them – keeping them closer within reach. It is no wonder that unintentional shooting deaths by children rose by nearly a third last year.

The increase in gun purchases is also a bad recipe when it came to the isolation that COVID brought and the resulting increase in domestic violence that has been reported. The Domestic Violence Hotline said they received the highest incoming volume calls that they have ever received -- over 636,000 calls, chats, and texts during 2020, and nearly 20% of the callers noted that they were experiencing a threat from a firearm.

In public health, and as internists, what can we do?

One doctor by the name of Gary Slutkin, MD is trying. He started an organization called CURE Violence Global. His belief is that violence should be treated like a disease, one that is contagious and in fact genetic. Dr. Slutkin is an infectious disease expert who is the former head of the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Intervention Development Unit. He launched his organization in West Garfield Park, which is one of the most violent communities in Chicago. After his organization began working in that community, there was a 67% reduction in shootings the first year.

They believe that “violence behaves like a contagious problem. It is transmitted through exposure, acquired through contagious brain mechanisms and social processes, and it can be effectively prevented and treated using health methods. To date, the health sector and health professionals have been highly underutilized for the prevention, treatment, and control of violence.” Cure Violence Global's goal is to help individual communities implement violence prevention programs to significantly reduce violence.

I looked at their approach and here are the methods and strategies they are using:

- Detecting and interrupting conflicts,

- Identifying and treating the highest risk individuals

- Changing social norms

I love that Dr. Slutkin is taking action from a unique perspective as a physician – that violence is a public health issue that must be healed. The Cure Violence model is based on the fundamentals of chronic disease management and changing behaviors to focus on detecting and interrupting potentially violent conflicts such as helping to prevent retaliations after a shooting happens and mediating ongoing conflicts. They also work to identify and treat those at the highest risk of committing violence and helping them attain the social services they need. This group uses individuals to engage community leaders to help mobilize the community to change norms. They’re partnering in cities across America including Atlanta, New York, Philadelphia, Washington, DC, and my city of New Orleans. Beyond the borders of the U.S. they are also working with other countries such as Mexico, Honduras, Brazil, Jamaica, and others.

As physicians – especially as osteopathic internists who practice Principle-Centered Medicine™, we need to practice the principles of deep listening with our patients to keep our eyes and ears open so we can spot things like domestic violence. We need to recognize patients we suspect are involved with violent individuals or are stressed and trending toward acts of violence. Knowing our patients is a big part of how we practice medicine as osteopathic internists, and when you view the treatment of violence as trying to rid a public health threat it is clear that as healthcare providers, we have a role.

If you want to know more about Dr. Slutkin’s work go to www.cvg.org or watch his awesome TED Talk.

Resources:

- 2020 Ends As One of America's Most Violent Years in Decades | Time

- Why gun violence rose in 2020, amid pandemic lockdowns (msn.com)

- Racial discrimination is linked to suicidal thoughts in Black adults and children (theconversation.com)

- Despite stress of pandemic, U.S. suicide rate dropped in 2020 (medicalxpress.com)

- Why did gun violence go up during the pandemic? | Salon.com

- Gary Slutkin: Let's treat violence like a contagious disease | TED Talk

- www.cvg.org

- https://twitter.com/noisefiltershow/status/1457765881711185924?s=11